A unique team of medical professionals is hitting the streets of Stockton, offering an alternative to only sending armed police officers to assist people dealing with a mental health crisis.

The city’s Mobile Community Response Team (MCRT), which recently completed the first of a three-year pilot program, is composed of outreach specialists, licensed clinical social workers and medical assistants.

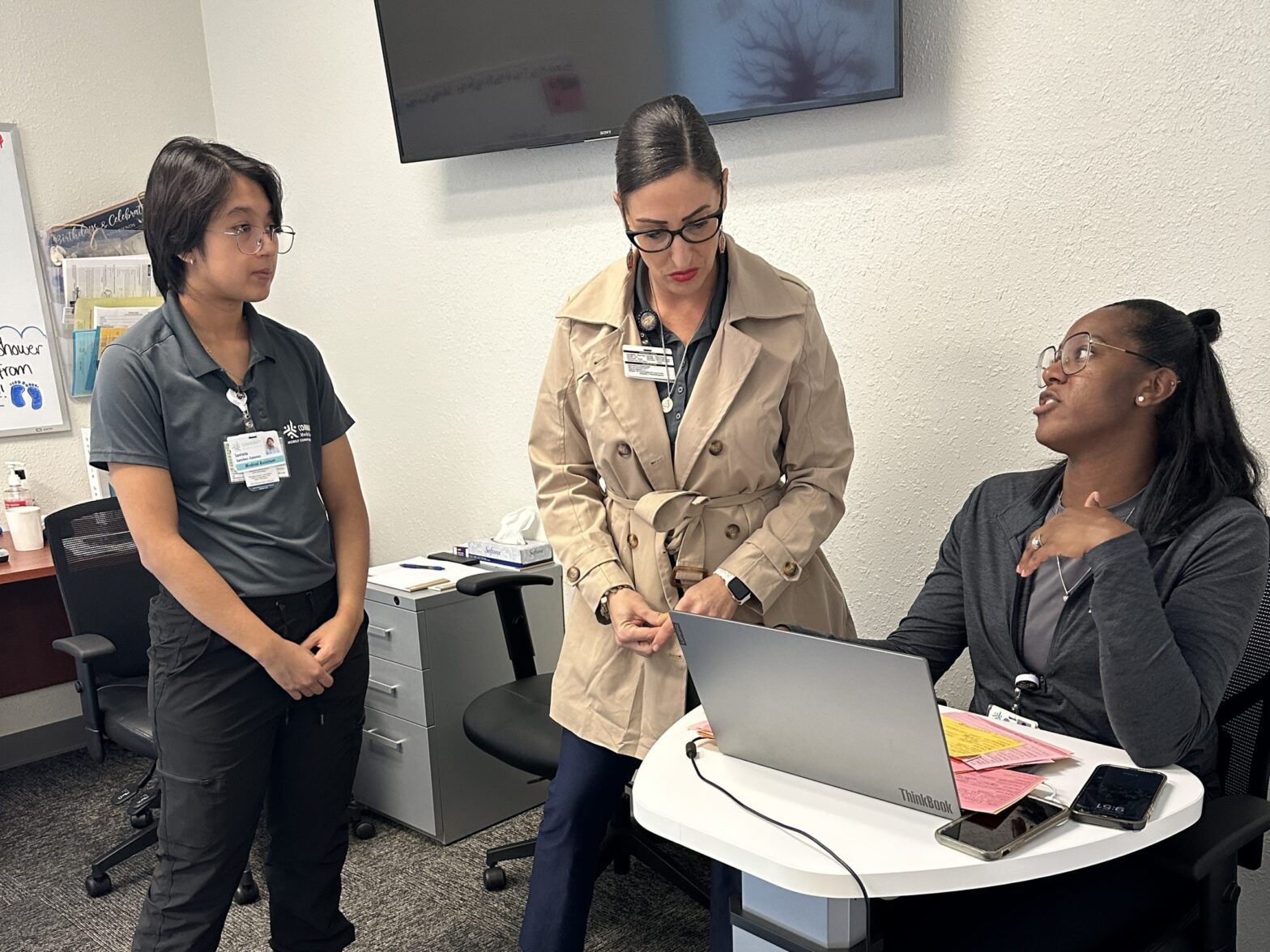

CVJC recently went on a ride-along with the team to see them in action. The team works in partnership with Stockton police to respond to certain incidents like domestic disputes, self-harm and behavioral health situations.

“When you’re in the thick of it, the first encounter is about stabilization and safety,” said Torrie Piasecki, a Community Medical Center/MCRT behavioral health clinical supervisor and licensed clinical social worker.

When her team arrives at a scene, she does everything she can to ensure the community member is comfortable talking over the situation, either one-on-one or with a support person present.

“Initially, when we’re going out and someone is in a state of paranoia, or someone is not themselves, we’re going in to de-escalate and to stabilize,” Piasecki explained. “We’re just going in to give some intervention, so that person can be OK. The priority’s always safety. And then when we do (a 48-hour) follow up.”

An arm of the Community Medical Centers’ CareLink mobile health department, the response team was created to solve situations that might be better served by someone trained in behavioral health, rather than just relying on police.

“We can’t, we don’t, forcefully detain anybody,” said Lindsay Lopez, MCRT project manager.

“But we do have the ability, if somebody wants to go (seek treatment), to take them in the vehicle so that their family is not forced to take a different route or have to take them themselves.”

The other route, Lopez said, would be for law enforcement to take the community member in crisis to a 72-hour involuntary lockup at San Joaquin County Behavioral Health.

How it got started

MCRT was made possible by community organizations who noted Stockton’s need for community-led mental health intervention.

Faith in the Valley, a nonprofit spanning five counties, began the C.A.L.L Stockton Initiative in 2020, the year many communities across the country sought out solutions to police brutality following the killing of George Floyd.

C.A.L.L. (Call Assistance Lifeline) is the foundation for MCRT’s work.

In a video detailing the initiative, residents from communities of color explained the need for a program like MCRT stems from their concerns on how easily police tension can turn to violence in a diverse region like Stockton.

“The data shows a need for this in our community and that the utilization by the community is increasing,” Stockton Police Department spokesman Omer Edhah wrote in an email statement.

In 2022, San Joaquin County’s Community Health Needs Assessment report listed “mental health” as the highest priority concern in the area.

Currently, when a caller dials 911 to report a public disturbance or potentially dangerous mental health crisis, police will arrive first and make a decision whether to call MCRT.

“At this time, there are no plans for the department dispatch to send MCRT to an incident without an officer first responding to evaluate for safety,” Edhah said.

Members of the public, however, can also call the program directly if they need assistance. “It doesn’t hurt to call,” said Piasecki.

“We will answer the phone and your questions. If we are not the team that can come out and assist you, we can direct you to who can.”

Assisting those in need

Earlier this year, Piasecki and her team intercepted a patient who had left his family a detailed note on how and when he planned to commit suicide.

They learned it was not his first attempt. “It was a very serious, but good interaction,” Piasecki said. “While we were there, after about an hour, he declined any self harming feelings.”

Her work with that patient didn’t end there. Piasecki said she contacted County Behavioral Health to get him assessed for intake, and learned he was open and willing to the process.

Unfortunately, CBH services were unable to immediately respond, so she had to come up with another plan.

“Because he wasn’t actively suicidal (after our meeting), we didn’t call the police,” Piasecki said. “But we did go back out the next day and offered him the opportunity to take him (to CBH) on his own terms.”

The behavioral health branch of Community Medical Centers, in partnership with Faith in the Valley, the nation’s oldest mobile mental health service, CAHOOTS, and the city, also created the MCRT program to fulfill city spending goals for Measure A and American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) funds.

The team is growing, Lopez said. The program eventually plans to be available 24 hours a day, seven days a week. For now community members can reach them daily from 8 a.m. to 11 p.m.

In order to function around the clock, MCRT is actively recruiting to fill the team with 14 full-time CMC employees. A team usually consists of a social worker, medical assistant and a case manager.

And Stockton isn’t the only Valley community using behavioral health professionals to assist law enforcement. Mobile mental health teams are being used as alternatives to police intervention in Modesto, Merced and Fresno.

Meeting people where they’re at

In a diverse community like Stockton, MCRT regularly runs into patients who don’t speak English. In most cases Spanish-speaking team members like medical assistant Lavinia Sanchez-Jimenez, a recent Delta College graduate, step in to translate for MCRT mental health providers.

When someone is having a mental health crisis and doesn’t speak Spanish or English, the team uses AMN Healthcare’s Stratus services, which puts them in contact with a translator, according to Piasecki.

Behavioral health services can look very different from case to case. During MCRT’s morning meeting on Nov. 17, Piasecki, Lopez and Sanchez-Jimenez talked over 18 open cases and were alerted to three more potential patients by other CMC providers.

It’s Piasecki’s job to assess each patients’ history with the group and determine which visits can be done over the phone and which need in-person check-ups, always while waiting for police dispatch to request a mobile team.

The team often finds patients when Stockton police alert them, community members call their hotline, or another CMC provider initiates a “warm-handoff” – which is alerting them to potentially suicidal or qualifyingly depressed people within the network.

Because the team is part of the larger CMC network, patients are able to get extended care for just about any mental health issue.

Piasecki said two of the team’s open cases that day began as concerned parents calling to get help for their kids.

One Spanish-speaking mother reached out with concerns about her son’s depression. The boy is not attending school, likely due to bullying, Piasecki said.

Members of the MCRT are now planning to help the mother write a letter to the principal of her son’s school asking for an education plan and bullying policies. They also will accompany her to speak to school officials.

The other was a mother requesting treatment for herself, after initially asking the team to visit her daughter.

“Sometimes when a family member is dealing with a mental health crisis,” Piasecki said, “they’re also affected. We offer support however they need it.”

Other patients not explicitly looking for mental health help get connected with Piasecki’s team. For example, an unhoused woman, new to Stockton, was found unconscious and taken to a hospital. MCRT was then alerted to her situation and went out to check on her mental state after the incident.

“When we initially sat down with her she said, ‘If a provider could come to me, that would be amazing. I didn’t know about the service, I don’t know much about the area,” Piasecki recalled, “But obviously if she’s intoxicated, she’s going to be a different person.”

Piasecki learned the woman deals with seizures and substance abuse. During that first meeting, the woman told the MCRT she could use help from behavioral health services, but then later refused to sign paperwork that would ensure her care.

Piasecki and the team made a note to look for her later that day to attempt to get her to sign up for services when she’s sober.

Lopez said such cases are interesting because it gives the team an opportunity to work with the whole CMC CareLink network to get the patient comprehensive care for all aspects of their health, not just mental.

Most of the patients are billed through MediCal, Lopez said. But MCRT helps people with private coverage find resources within their own networks. When a call from the police connects them with any community member in crisis, the team assists, deescalates and reassures them before jumping into the logistics.

Tracking progress

Within the next six months, the MCRT program will present a cost analysis report showing how much money the city saves when the team responds to domestic disputes and mild/moderate mental health crises, instead of officers.

In late September, Lopez presented the MCRT’s response data collected over the summer to the Stockton City Council.

The numbers show MCRT received over 1,500 calls in from June to August, mostly from community members requesting service. During this time, the highest number of calls were in response to white and Hispanic individuals in the 18-30 year age range.

Data shows many people assisted by the MCRT this summer were in the 95207 code, which roughly extends from West Hammer Lane to Brookside, and Interstate-5 to West Lane.

The total number of calls in October 2023 were 695, Lopez told CVJC.

You can reach the Mobile Community Response Team at (833) 311-2273 to request immediate support directly from them. The 988 Suicide and Crisis line can also direct you to the MCRT.

Vivienne Aguilar is the health equity reporter for the Central Valley Journalism Collaborative, a nonprofit newsroom based in Merced, in collaboration with the California Health Care Foundation (CHCF).