By MARIJKE ROWLAND

When Californians cast their votes for the March 5 primary, they will see only one statewide initiative on the ballot.

How voters decide on Proposition 1 will help shape the state’s policy toward fighting homelessness and providing mental health for years to come.

Supporters have said it will address the “sickest of the sick” among the state’s unhoused population, and help ease the state’s homeless problem by focusing on getting those people off the streets, as well as helping homeless veterans.

Opponents have said it will transfer money away from services that keep people out of homelessness in the first place, thus possibly exacerbating the state’s problems. They also say it’s an inefficient way to address the root causes of homelessness in California.

Here is a look at what is at stake in the Central Valley and how things would change – or not – with its passage or failure.

What is Proposition 1?

Prop. 1 is a complex two-part initiative that would represent a significant shift in how county behavioral health services funding is allocated, as well as approve $6.4 billion in bonds to build largely institutional treatment and housing facilities statewide.

What does it have to do with mental health?

Prop. 1 amends the state’s landmark Mental Health Services Act, passed by voters in another ballot initiative in 2004, which levies a 1% tax on personal incomes over $1 million. That “millionaire’s tax” money, which last year raised about $3 billion, has been used since to help pay for mental health services across the state, and currently accounts for about one-third of all such funding. The rest comes primarily from Medi-Cal and the general fund.

About 95% of MHSA dollars are distributed to counties which then have a considerable amount of leeway to use the funding to pay for their core services ranging from prevention, early intervention and outreach programs to supporting community-based organizations. The other 5% goes to the state for administration.

San Joaquin County received $51.7 million in MHSA funding so far this fiscal year and neighboring Stanislaus County received $37.5 million, according to the Mental Health Services Oversight & Accountability Commission. Nearby Merced County got $21.5 million this fiscal year.

How would it change the Mental Health Services Act?

Prop. 1 amends the MHSA to direct how counties can use their funding. It would require 30% of funds, or roughly $1 billion statewide based on last year’s figures, to go to housing intervention programs.

That’s a major change in how counties typically budget MHSA dollars. About 50% of those housing funds would be directed toward the “chronically homeless” with a focus on encampments, the other half would be for those with mental health and/or substance abuse disorders.

Housing programs could include rental subsidies, transitional housing, shared housing, family housing, housing projects and more. The housing funds cannot be used for mental health or substance abuse treatment services.

The remaining 70% of county MHSA funds would then need to be split between full-service partnerships (35%) and behavioral health services and support (35%) including workforce education/training and early intervention programs.

It would also change the name of the MHSA to the Behavioral Health Services Act (BHSA) moving forward.

What kind of services would potentially lose MHSA/BHSA funding if Prop. 1 passes?

While it is not explicitly spelled out in the proposition, county behavioral health services would need to reallocate about a third of their funding exclusively toward housing programs. Funding awarded to community-based organizations could be at risk, including prevention and innovation grants which often go toward peer-to-peer services that offer early intervention and recovery support.

Opponents have argued that funding for LGBTQ+ and BIPOC groups that provide mental health services like counseling and other resources could be in jeopardy. The initiative encourages counties to move some of their early intervention to Medi-Cal billable services, which could require clinical staffing, to make up for some of the gaps.

Some programs, like the nonprofit Peer Recovery Art Project in Modesto, fear their funding could be cut entirely. Founder and CEO John Black has received innovation and prevention/early intervention grants from the county through the MHSA over the years to provide recovery support, support groups, art installations and other events. His most recent grant is for $12,000 to $15,000 a year. Without that, he said he would have to give up his downtown gallery and meeting space.

“This is part of a long line of taking away recovery dollars. People getting proper support to stay healthy are that way because of that proper support. But now they want to drop that,” Black said. “There are unique programs through MHSA that address those populations. But they could be losing some of their funding, including the LGBT movement which has been strong in the mental health area.”

Does Prop. 1 raise taxes to pay for the MHSA/BHSA changes, housing programs?

No, it does not. The “millionaire’s tax” will not be increased to fund the changes to MHSA/BHSA. But, if passed, the bonds would come out of the state’s general fund, which uses tax revenue.

What will the $6.4 billion in bond pay for?

The other part of the initiative is the bond measure, which would issue $6.4 billion to finance the building of permanent supportive housing as well as voluntary and involuntary behavioral health treatment for those with mental health or substance abuse disorders.

Some $4.4 billion in the bonds would go toward treatment facilities, for both voluntary and involuntary programs. The other $2 billion would be to build or renovate housing for those experiencing homelessness, mental health and/or substance abuse disorders. County officials, community-based organizations and private builders can all apply for the bonds.

The Legislative- Analysis Office estimates the bonds could pay for some 6,800 treatment beds and 4,350 housing units. Roughly half of those housing units (2,350) would be reserved for veterans experiencing homelessness.

How many homeless people and veterans are there in California? What percentage would Prop. 1 help find housing?

According to count numbers from 2022, the state has some 171,500 unhoused people. About 10,400 of those are veterans. Prop. 1 has a potential to house about 2.5% of the overall homeless population and about 22.5% of the homeless veteran population.

Wasn’t there already a proposition passed to create housing for homeless people experiencing mental illness?

Yes. In 2018 California voters approved “No Place Like Home” – also known as Prop. 2 – which greenlit the use of some $140 million in annual MHSA funding to help repay $2 billion in bonds. That money is being used to create housing for homeless people with mental illness.

The Legislative Analysis Office estimated the bonds would help build “roughly 20,000 supportive housing units.”

But a recent CalMatters investigation has found that five years later, No Place Like Home has finished just 1,797 units across the state.

In northern San Joaquin Valley counties, less than 50 completed housing units have been built from No Place Like Home funding as of Feb. 2 of this year, according to the CalMatters report. Stanislaus County received $11.7 million and has completed 48 units of a planned 73, San Joaquin County received $2 million and completed zero units of a planned 18 and Merced County received $10.6 million and completed zero of a planned 31 units.

San Joaquin County has since completed an affordable housing project, the Sonora Square Apartments in Stockton. The complex, which has 37 one-bedroom units and a managers unit, used $2.1 million in No Place Like Home funding as well as other sources to provide housing to those experiencing mental health issues and homelessness. Tenants began moving in December 2023 all rooms are now filled.

Stockton’s Sonoma Square was not listed among projects in the No Place Like Home annual report referenced by CalMatters because projects must be occupied for 90 days to be classified as “completed.”

How is this related to other recent mental health legislation passed in the state, including CARE Court and SB 43?

Prop. 1 is not explicitly connected to CARE Court, which creates a voluntary pathway for people to receive county behavioral health services through the judicial branch, and SB 43, which expands the definition of “gravely disabled” and thus the number of people who can be forced into involuntary treatment for mental health or substance abuse disorders.

But the three pieces of legislation would work together to give state, county and city governments more authority to treat and house those with severe mental illnesses and substance abuse disorders through voluntary and involuntary means.

Who is supporting Prop. 1?

Gov. Gavin Newsom has championed the initiative, lending his name and considerable political muscle to the Yes on 1 campaign. The changes to the MHSA were largely authored by Valley-based State Sen. Susan Talamantes Eggman, D-Stockton, who also authored SB 43 which expands who can be involuntarily treated for mental illness or substance abuse issues.

Other top funders include Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria, Sutter Health and State Building & Constructions Trades Council of California. Other major organizations endorsing Prop. 1 include National Alliance on Mental Illness California, California Correctional Peace Officers Association, California Professional Firefighters, California Association of Veteran Service Agencies, California Hospital Association, Kaiser Permanente and SEIU California.

The campaign has raised $12 million, and ran a local network advertisement during the Super Bowl telecast earlier this month.

Who is opposing Prop. 1?

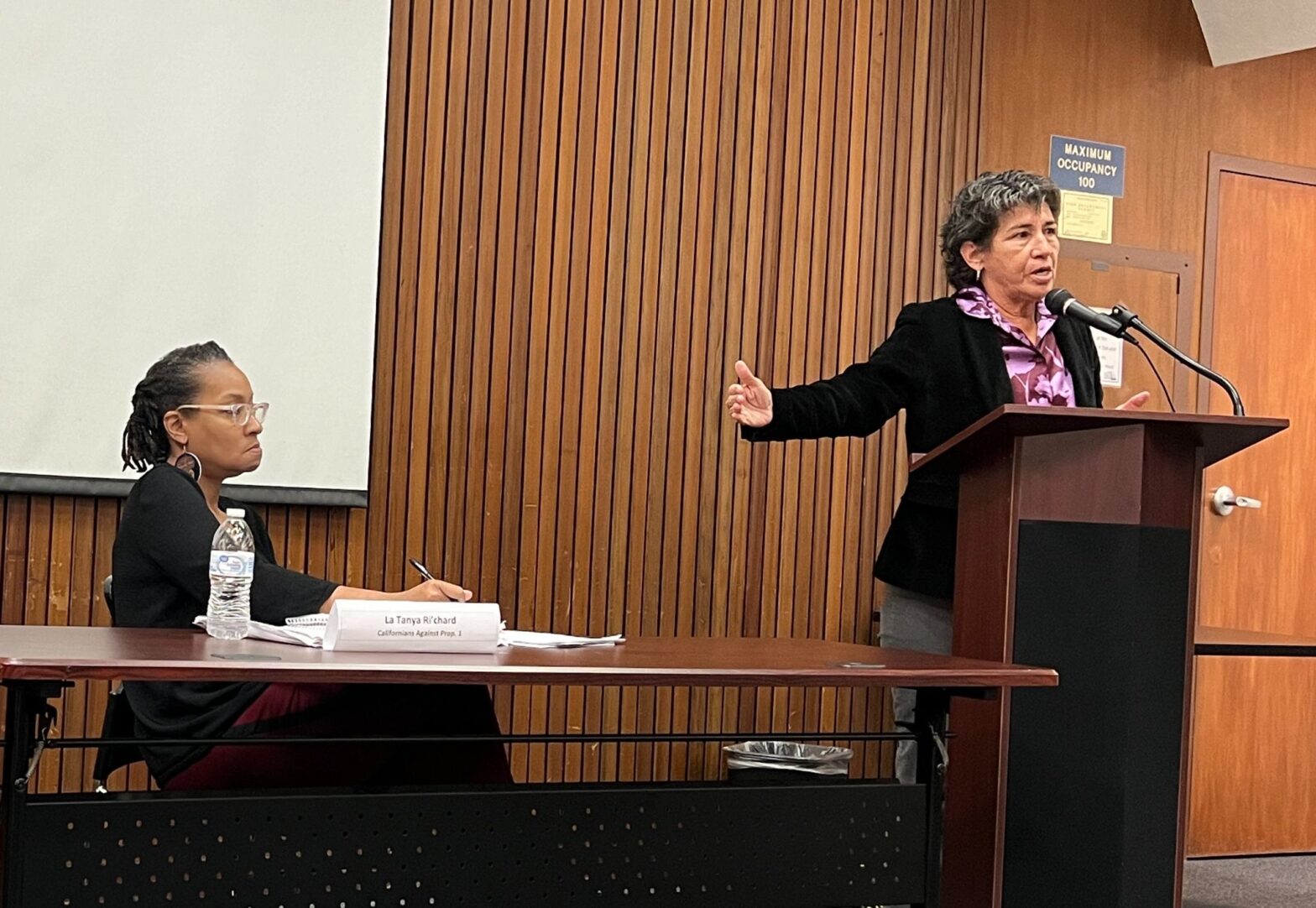

Californians Against Prop. 1 is largely a grassroots campaign and includes many people working in the behavioral health field currently.

The opposition campaign has been endorsed by the League of Women Voters of California, Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Association, Disability Rights California, Mental Health America in California and Cal Voices.

The campaign has raised $1,000.

What are the key arguments for Prop. 1?

Homelessness is an increasing crisis across the state, as anyone who has passed by an encampment or encountered someone in a psychotic break on the streets can attest. The state has the highest rate of unsheltered homeless across the country, with 67.3% of its homeless without a safe or sanctioned place to sleep, according to a 2022 Department of Housing and Urban Development report.

Mental health issues are highly prevalent among unhoused Californians, with about two-third (66%) reporting some form of mental health disorder from depression to anxiety to hallucinations, according to a 2023 University of California San Francisco study. But only 18% have received any non-emergency mental health care.

Supporters say the state’s current approach to mental health services, particularly for its most severe cases, is simply not working. Prop. 1 would shift more services toward the chronically homeless, or or the “sickest of the sick” as Eggman has described them, including the people living in encampments with serious mental illnesses or drug addiction.

The proposition would create more guidelines for how counties could spend their MHSA/BHSA funding, instead of giving them wide latitude and allowing for different approaches across regions. The first major change to the MHSA in its 20 years is needed, they say, to ensure better efficiency and prioritization by the counties.

“I would hope nobody here is arguing that we maintain the status quo, because the status quo is not acceptable for you, for the people that you treat and for the general public who are saying ‘y’all have to do something,’” Eggman said at a public forum on Prop. 1 in Stockton earlier this month.

What are the key arguments against Prop. 1?

Opponents of Prop. 1, including many people in the behavioral health field, believe the changes could worsen the state’s overall homeless crisis. Early intervention, recovery and peer support services, often provided by community-based organizations, could be cut thus resulting in more people falling back into their illnesses.

“You’re gonna make the mental health crisis worse. If you can’t get help you lose hope in yourself. People will end up missing days of work, which is going to make them at risk of losing their housing. So what’s also going to create a bigger housing crisis,” said LaTanya Ri’Chard, a Merced-based peer support specialist with the Californian’s Against Prop. 1 campaign.

Studies have shown that mental health issues, while highly prevalent among the unhoused population, are not necessarily the root cause of the state’s homeless problem. Instead, loss of income and the state’s affordable housing crisis are the greatest drivers of homelessness, according to the 2023 UCSF study.

Opponents are also concerned about the bond measure’s creation of more involuntary treatment facilities, which they believe could potentially lead to people with severe mental health or substance abuse issues being locked away. They argue the proposition could return California to its pre-1967 Lanterman-Petris-Short Act days when those with mental illnesses were routinely involuntarily warehoused in state hospitals or psychiatric facilities.

“We have to recognize that just locking people up doesn’t solve our societal problems or our human condition. It just hides the problem,” said Paul Simmons, co-founder of the Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance and part of the No campaign.

How would Prop. 1 be administered if passed?

The state would administer the changes and oversight, and would increase its percentage of millionaire’s tax funding from its current 5% to 10%. That would result in about $140 million staying with the state instead of the counties.

If passed, how long would it take for the initiative’s changes to go into effect?

If the initiative passes this March, counties will have an 18-month transition window to enact all of its changes. The proposition must be in full effect by July 1, 2026 in all counties.

San Joaquin County Behavioral Health Director Genevieve Valentine said it is expected to cost the county $1.7 million in administrative costs to make the necessary changes in both infrastructure and transparency to enact all of Prop. 1. Of that, $900,000 would be ongoing annual administrative costs.

Stanislaus County Behavioral Health and Recovery Services Director Tony Vartan declined to comment or answer questions on Prop. 1, citing California Government Code 3206 which prohibits public officials from “participating in political activities of any kind while in uniform.”

Marijke Rowland is the senior health equity reporter for the Central Valley Journalism Collaborative, a nonprofit newsroom, in collaboration with the California Health Care Foundation (CHCF).